Aeneid 4.2. Roman understanding of being: production

Summary 18 # Man, God, and Society in Western Literature - From Gods to God and Back

Virgilius was a Roman poet and a friend of Augustus Caesar, the first emperor (he became emperor in 27 BC). Virgilius lived between 70 and 19 BC, and his birth year is 400 years after Aeschylus. Jesus, on the other hand, was born 19 years after him. He was considered a proto-Christian.

His book The Aeneid is about Aeneas, who flees from Troy when it is destroyed and goes up in flames. He left the city with his father, wife, and son (these people have various names in the book, much like in Dostoevsky’s novels).

The Gods in The Aeneid are adopted from the Greeks, but now they have different names. Zeus becomes Jupiter, Hera—Juno, Aphrodite—Venus, Poseidon—Neptune, Hermes—Mercury, Ares—Mars, Athena—Minerva.

As discussed in blog 4.1, the two previous ‘understandings of beings’ were ‘phusis’ as ‘bursting forth’ or ‘welling’ and ‘whoosing up’ in the Homeric-Greek world. Gods, moods, storms. They are so powerful that you cannot cultivate. Let alone that you could dominate them. Therefore, the only response is one of awe and wonder.

Subsequently, the understanding changed to ‘poiesis’ in Aeschylus. ‘Poiesis’, which is a form of ‘cultivation’, ‘nurturing’, and ‘bringing forth’ of things so that they present themselves at their best (the classical Athenian world). This is an expressive order. Thus, in the Oresteia, the Furies are cultivated at their best – after being long suppressed in the world of Homer – so that they become the ‘Humanities’.

The following and new Roman ‘understanding of being’ is close to our own understanding’. This can be described as imposing a form on matter for the sake of production. It is not about bringing out the intrinsic nature of things, which would be poiesis.

It helps to see this ‘understanding of being’ by looking at what they had a lot of. These were bricks, amorphous matter without an intrinsic form, to which they could impose their own structure as needed. These are ‘bricks’. With them, you produce roads, houses and aqueducts.

The architecture and infrastructure was very solid, just like the Roman Empire. If we leap forward, we also like to impose a form. However, we also like flexibility, that things can change form if we wish. Therefore, for us, it is not bricks, but plastic that is important in postmodern culture. We can melt it and make something else. The ultimate for us is the digital world, where everything is malleable.

Now, when we look at the Aeneid from this understanding of being as ‘productivity’ and compare it with the Oresteia, we notice that Aeschylus almost seems possessed by his work. It feels as though he is almost out of control. He writes wildly, but almost like a medium, writing down what makes Athens so special.

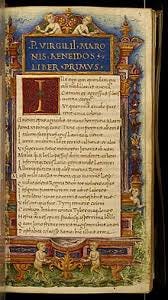

Virgil, on the other hand, is hired by Emperor Augustus as a kind of public relations figure to explain to the Romans what life is about and where their origins lie. In return, he can live a good life thanks to his productive work. This is reflected in the style of the Aeneid: he is not wild and out of control. Virgil knows what he wants to write and works it out, without the wonder of an Aeschylus who, through his struggle with the material, slowly experiences in awe what makes Athens so special: its legal system and inspired patriotism. Virgil primarily does his duty as a citizen. Nevertheless, it is a ‘work of art’ that ‘worked’ for the Romans. They saw it as a god, learned it by heart. It was, for them, a sacred object for which they built altars."