Oresteia 3.1: Tendency to monotheism in Athens

Summary 9# Man, God, and Society in Western Literature - From Gods to God and Back

After having examined the understanding of being of the Homeric Greeks through the Great Work The Odyssey, we will now explore a new understanding of being. That of the classical Greeks, specifically the Athenian population around the 5th century BC. We will do this by examining the work of art The Oresteia by the tragedian Aeschylus.

This work is both more difficult and easier to read compared to The Odyssey. In reading The Odyssey, one had to read between the lines because we were interested in what it meant to live in a polytheistic culture. Meanwhile, Homer takes this as a given—his understanding of being—while focusing on telling the story of Odysseus. For instance, we paid much attention to the affair between Paris and Helen, even though it occupies only a page.

What makes reading Aeschylus easier is that we probably read The Oresteia in much the same way as the Athenians did. We understand that it is an exploration of the relationship between humans and gods, and between the gods themselves. In the tragedy, every detail matters; it is a coherent whole.

Aeschylus was very popular in his time—the equivalent of a modern academic award winner. He won the prize for the best Athenian play every year in a row. Thus, his work became a cult classic, performed repeatedly year after year. However, what makes reading Aeschylus more challenging compared to Homer is the simplicity of Homer’s style. Aeschylus is much more complex and profound. He makes various references to myths, the past, and the present. These references were familiar to Athenian audiences but are more difficult for us to understand today.

It is now crucial to be very aware that there is a completely different understanding of being at play. Although the gods have the same names as in Homer, they are fundamentally different. This is a crucial premise for this entire course: no word, concept, or object that appears similar across different historical periods is, in essence, the same. A god, therefore, is something entirely different in Homer, Aeschylus, and later in Virgil or Dante.

We can now ask ourselves: what are gods here? They are no longer mere moods, as in The Odyssey. Rather, they are cultural values or practices. Ways of acting that everyone in the culture considers normal, providing orientation for human behavior. They show what is right and wrong. The gods provide that framework. And when different practices clash, there is a conflict between two or more gods.

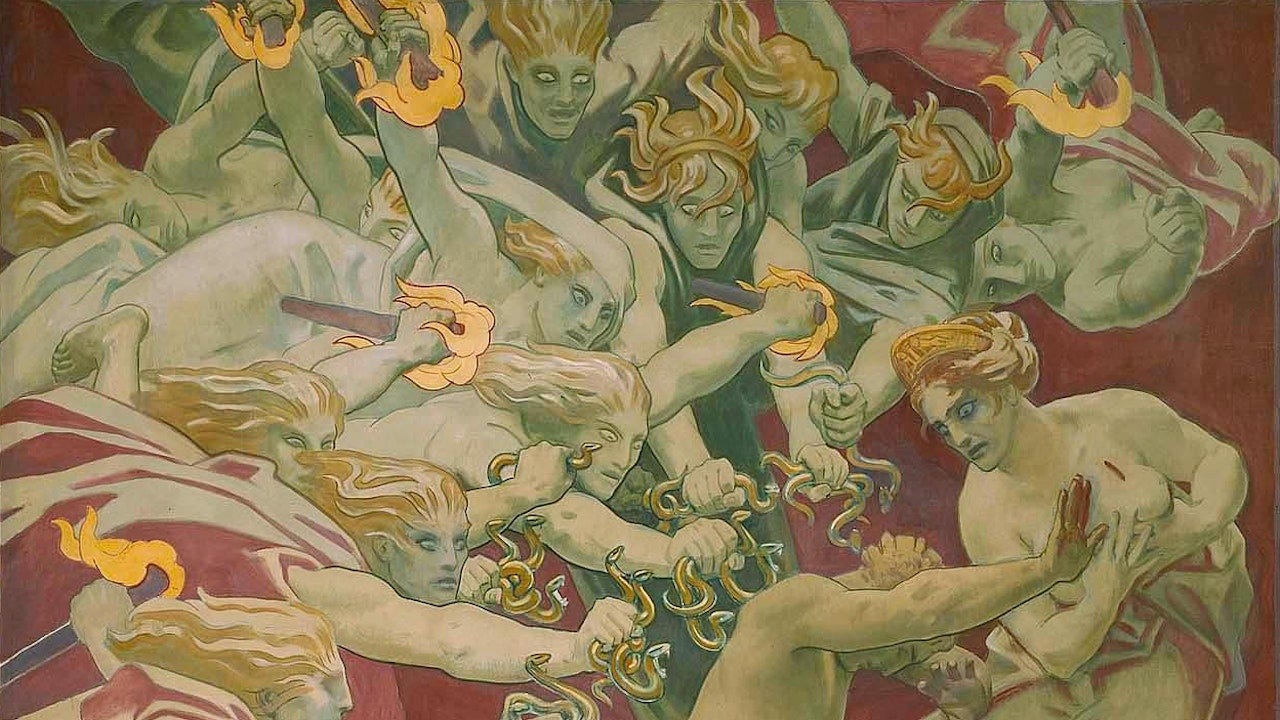

This is exactly what happens in The Oresteia: the gods are in conflict with each other. We don’t see this in Homer’s polytheistic world. Yes, gods play tricks, do things behind each other’s backs. But there is no genuine mutual hatred or strife. In Aeschylus, there is no longer polytheism, no plurality of gods. There are two camps of gods: on one side, the Furies, the goddesses of vengeance, and on the other, the gods of the pantheon. And between them, there is conflict. This is not yet monotheism, but it is also no longer polytheism. It is a kind of 'bi-theism' because there are two powers. But the historical movement is towards monotheism.

The dramatic question is: who are the true gods? It is about who represents the true values. This would never happen with Homer: Aphrodite does not believe that everyone should be swept up by erotic love, just as Ares does not believe that everyone should be carried away by a violent mood.